You will often hear the term “magnitude” in Astronomy. Have you ever wondered what it meant? In this article, we’ll try explaining this term and we’ll see how to use correctly the “apparent magnitude” or “absolute magnitude” when talking about astronomic objects in the sky.

What is magnitude?

To keep things simple, in astronomy, “magnitude” refers to the brightness of an object in the sky. What we need to be particularly careful about, is the fact that the brighter the object, the smaller its magnitude! For example: a star with magnitude 1 is brighter than a star with magnitude 2! …And you guessed it, magnitude is unitless, that’s why we say “magnitude 2” or “2 magnitude”.

Apparent and absolute magnitude

Let’s imagine that we are on the top of a hill and we look at a very distant street light, down in the valley; let’s say this street light is 5 km away. From the top of the hill, we can see that the light is of a certain brightness. Now, imagine we start walking towards the street light. As we approach it, it seems that it gets brighter and brighter. So, how can we quantify the brightness of the street light if it seems to vary in function of where we are, relative to it?

In Astronomy, this issue is addressed by using two types of brightness – or, more correctly, two types of magnitude – for a celestial object: its apparent magnitude and its absolute magnitude. Most of us – at least in the near future! – will probably see the Moon, the stars, the planets and any other bright object in the night sky from our own planet, from Earth. All these objects will have a certain brightness, as they are seen from Earth, and this brightness is characterized by the apparent magnitude. So, the apparent magnitude of an astronomical object is the brightness of that object as seen from Earth.

As for the absolute magnitude, it is defined as the apparent magnitude of an astronomical object, as seen from a distance of approximately 310.000.000.000.000 km (the equivalent of 10 parsecs). The “usual” astronomer will just stick to the apparent magnitude; however, the absolute magnitude is important in research and studies, for example, for comparing the “real” luminosities of two or more objects.

Also, when talking about just “magnitude” – thus without specifying “apparent” or “absolute” – it’s the apparent magnitude which we refer to.

Magnitude values

Remember that a lower magnitude means a brighter object. But brighter of how much exactly?

The magnitude scale is logarithmic. Which means that the values which are to be displayed and compared on this scale are very far apart: the largest numbers are very much larger than the smallest numbers to be compared. To get a sense of it, magnitude 1 is 100 times brighter than a magnitude 6 (and not just 6 times brighter, as it would be the case on a “normal” scale).

Here are a few examples of magnitudes, to get an idea how this works:

- The Sun has a magnitude of -27

- The full Moon has a magnitude of -13

- The International Space Station, when brightest, has a magnitude of -6

- Planet Venus, when visible and when brightest, has a magnitude of -5

- Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, has a magnitude of -1

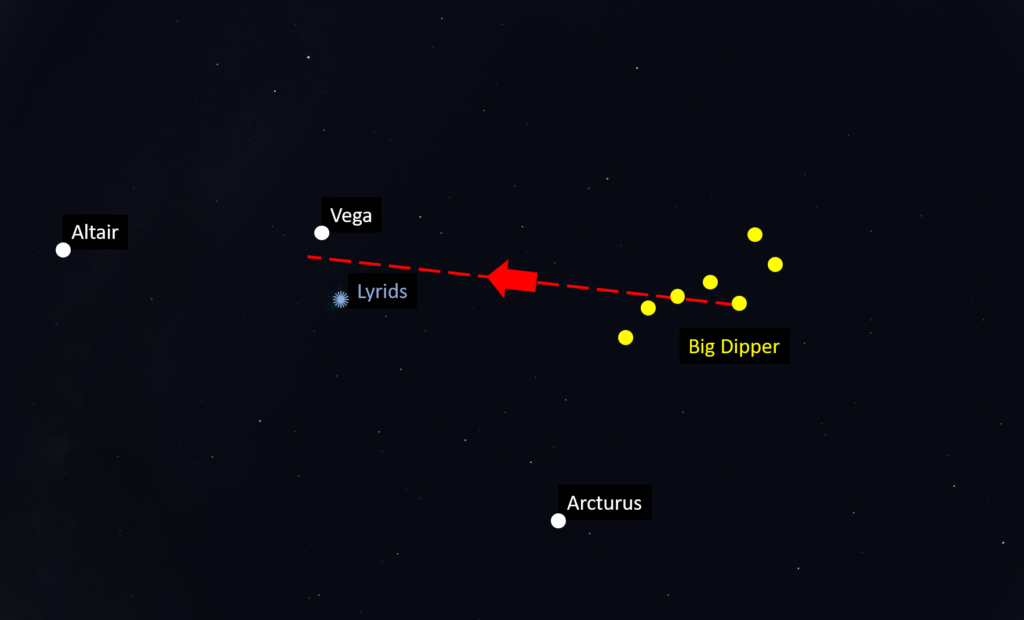

- Vega, the brightest star located in the Lyra constellation, has a magnitude of 0

- The human eye, unaided, can normally see up to magnitudes of +3 – +6 (in function of the light pollution)

Can you now imagine how much brighter is the Sun (of magnitude -27), which you can’t even look directly at, compared to a Full moon (of magnitude -13)?

Magnitudes can be negative or positive, and the same rule applies: lower the magnitude – brighter the object.

And you guessed it: all “bright” objects have a magnitude, even the Sun, natural satellites or artificial objects (such as the ISS)!

The star Vega, besides being one of the brightest stars in the night sky and besides guiding us to find the Lyrids meteor shower each year in April, is also the reference point on the magnitude scale, having a value of 0.